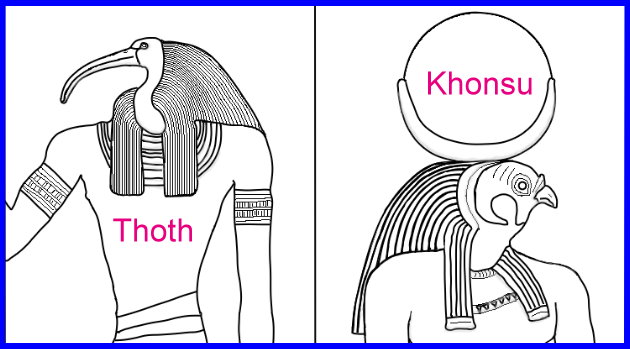

Although the ancient Egyptians had many gods, the deities they associated with the sun and moon were among their most important. Their calendar systems were solar, but they based many festivals on the lunar cycle. Their two primary lunar gods were the full moon deity, Khonsu, and the dark moon and the first lunar crescent god, Thoth.

Imagine yourself in the place of an Egyptian three millennia ago. When would you have festivals for Khonsu and Thoth? A common-sense answer would be that they must have celebrated the full moon god when the moon was full. They could have their Khonsu feasts after dusk while the moon reflected beautifully off the Nile River, the canals, and reservoirs. Although Thoth festivals were less frequent, they must have had them when the first crescent appeared.

Unbelievably, this common-sense deduction is the opposite of the scholarly consensus: Their understanding places Khonsu festivals on dates when the moon was dark and Thoth festivals when the moon was full. (I am not making this up!) Why did they adopt this idea? Some Ptolemaic Era inscriptions in the Edfu and Dendera temples (south and north of Thebes) show the priesthood had adopted this practice. Many Egyptians adopted the Macedonian lunar calendar when the Ptolemaic Dynasty began to rule over Egypt. This change included reversing the traditional associations of their lunar gods with their festivals. Nevertheless, this practice was not ubiquitous in Egypt.

The transliteration of the Egyptian word for the first day of the lunar cycle is psdntyw. Ancient records containing psdntyw are rare. Fortunately, it occurs twice in the royal inscriptions of Thutmose III; they are Year 23, I šmw 21 (month IX) and Year 24, II prt 30 (month VI). These dates are 649 days apart, 21.977 average lunar cycles of 29.530588 days. How do we know these are full moon days, not dark moon occasions, as conventionally understood? The Upper Egyptians combined the Amun (solar god), Mut, and Khonsu Festivals (the Theban Triad), held monthly. Two Theban Triad Festivals were longer than the others, the Opet Festival and the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. Since Khonsu was the full moon god, these Triad festivals began on full moon days. The king’s “Annals Gift List” shows an Opet Festival that started on II Ꜣḫt 14 [Year 23] (month II). That date was 148 days after the I šmw 21 (psdntyw) event, precisely five lunar cycles later, proving that psdntyw, Lunar Day 1, represented a full moon.

During the New Kingdom Period, the Egyptians fixed the Wag and Thoth Festivals to the civil calendar dates I Ꜣḫt 18 and 19. However, during the Middle Kingdom and earlier, these movable festivals coincided with the first dark moon and lunar crescent after the peak of the annual Nile flood. A record from the reign of Fifth Dynasty King Djedkare Isesi shows that on one occasion, they celebrated both on I Ꜣḫt 26. This combined celebration implies that the unfixed Wag Festival was during or just after the dark moon. Just as the New Kingdom Amun Festivals began on a full moon, the Egyptians celebrated sun-god festivals (for Montu) on full moon days during the Twelfth Dynasty, as verified by documents from that era.

Scholar Rita Gautschy has identified the regnal years of many documents from Illahun with lunar festivals from the reigns of Senusret III and Amenemhat III. Four from Senusret III’s reign include two Montu Festivals and two Wag Festivals. The dates of the Montu Festivals are Year 6, II Ꜣḫt 14, and Year 8, II Ꜣḫt 22, which are 24.99 average lunar cycles apart. The Wag Festivals are Year 12, II šmw 22, and Year 18, II šmw 17, 73.99 lunar cycles apart. These dates place the Wag Festivals about half a cycle plus two days out of sync with the full moon Montu Festivals, demonstrating the Wag and Thoth Festivals were associated with the dark moon and first lunar crescent, as expected. One of those documents specifies that the Wag Festival was two days after the middle of the lunar cycle. This proves the Montu Festivals were at the start of that cycle on the full moon, psdntyw.

Thus, the pre-Ptolemaic celebrations of Khonsu and Thoth Festivals accord with common sense but are contrary to conventional thinking. A 35-page appendix in The Six Pillars (forthcoming) thoroughly discusses this topic.

3 comments