Many researchers approach the subject of historical chronology with the fundamental premise that ancient inscriptions have accurate chronological data. However, that is often not true. Investigators should not switch off their critical thinking skills because a document originated in the ancient past. A post on this website last year, “Common Sense and Divergent Chronological Records,” discussed ways to differentiate accurate from inaccurate ancient timeline data. This post considers some examples that illustrate that researchers should not credulously accept ancient sources as unquestionably truthful.

Another post last year, “Common Sense and the Mari Eponym Chronicle’s Eclipse,” showed that a later historian tried to reconstruct the Mari Eponym Chronicle (MEC) and mistakenly put a solar eclipse record some four decades too early. He failed to discern that the associated ‘birth of Šamši-Adad’ was figurative, not literal. Modern researchers have credulously followed his record down the same rabbit hole, even though, contextually, that interpretation makes no sense. Why do scholars accept that viewpoint? Because they reason, ‘That record is very ancient, and, therefore, it must be true.’ Nevertheless, that compilation likely originated centuries after the original MEC record.

By their very nature, king lists required repeated copying and updating as each monarch eventually died and a successor replaced him. Hand copying occasionally introduced errors. Virtually all ancient Middle Eastern king lists have inaccuracies in them. Therefore, unquestioning acceptance of their data without corroborating evidence is illogical. Nevertheless, astronomical records and international synchronisms provide much of the necessary confirmation of many second-millennium-BCE Assyrian and Babylonian king list records.

The Assyrian King List (AKL) exemplifies this type of problem. On the positive side, most of the extant regnal period data in the AKL is accurate in one or more of the three most complete copies of the AKL, but a few exceptions exist. For example, the two extant copies of the AKL that contain the regnal period of Išme-Dagan I (AKL #40) credit him with 40 years. Nevertheless, contemporaneous data show that his reign was some three decades shorter. (See the forthcoming The Six Pillars, Appendix E, “How Long Was Išme-Dagan I the King of Assyria? The Contemporaneous Evidence.”) He inherited the kingship over the city-state Ekallātum when his father (Šamši-Adad I) conquered Assyria. Moreover, since his father ruled Assyria for 33 years, we can surmise that most of his 40-year reign was as a vassal king of Ekallātum within the Assyrian Empire.

The Babylonian King Lists have similar problems. By examining the related dated business texts, Prof. John A. Brinkman found two mistaken regnal period figures on Babylonian King List A (BKL-A), one during the Kassite Dynasty and another during the eighth century BCE (Kudur-Enlil and Nabû-mukīn-zēri, respectively). In damaged parts, many kings’ names and regnal periods are missing from the BKL-A. However, one second-millennium king that ought to be in the intact part is missing altogether. (The second volume of The Astronomical Chronology will identify his name and ruling period.)

The AKL had a similar problem. The oldest copy, the Nassouhi King List, has a lot of damage and is largely unreadable. Nevertheless, it is more reliable in every case except for one where it preserves king list data contradictory to the two younger copies. The one exception is that it entirely skips the name and regnal period of one king, Shalmaneser II (AKL #93) and his reign of 12 years. Perhaps this omission and the one in BKL-A were missing lines only in these individual cuneiform copies. Nevertheless, the AKL had significant gaps of unaccounted years when Assyria was under foreign domination.

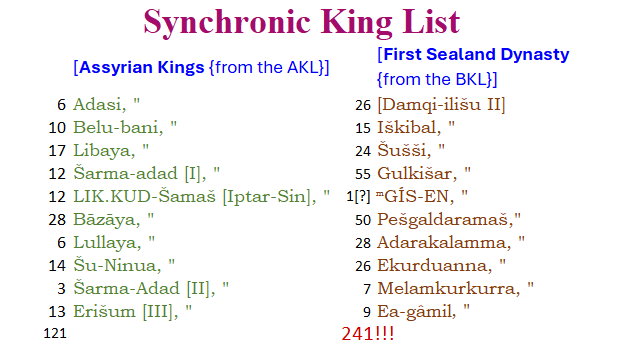

BKL-A lists the ruling periods of kings next to their names. In contrast, the first extant part of the Synchronic King List sets a list of Assyrian kings parallel to the Chaldean First Sealand Dynasty without tenure lengths. Comparing those two lists’ regnal figures from the AKL and BKL-A (illustrated above) reveals that this interval in the Sealand Dynasty is double the length of the supposedly synchronous period in the Assyrian timeline. In other words, the assumption that the Sealanders used “years” as units is incorrect, even though Babylonian scribes used years for the rest of the BKL-A. Instead, Sealand Dynasty officials listed ruling periods in half-years.

These examples illustrate that “ancient” does not necessarily mean “accurate” and that chronological researchers should seek confirmatory evidence.

One comment