Those kingdoms with relatively abundant chronological data from that millennium include Babylonia, Assyria, and Egypt. Let us begin with Babylonia because of the many anchors for its Amorite Dynasty’s timeline.

As discussed previously, the Middle Chronology model of the Venus Tablets of Ammi-şaduqa is correct and precise to the year. Archaeologists found seals from the reign of Assyrian King Šamši-Adad I in the remains of an ancient building in Acemhöyük, and both dendrochronology and radiocarbon dating indicate the approximate date those people had constructed that warehouse. Moreover, the timeframe for his tenure has a triple astronomical anchor. Šamši-Adad I was a contemporary and ally of Babylonian King Hammurabi. This synchronous period verifies the accuracy of the Amorite Babylonian timeline from Ammi-şaduqa back through Hammurabi.

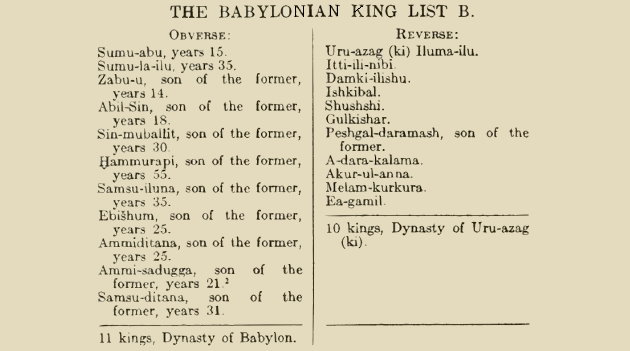

Babylonian King List B (BKL-B), illustrated above, includes five predecessors of Hammurabi, totaling 112 years. That list’s figures are often inaccurate and do not agree with the number of year names. Thus, Babylonian chronology before Hammurabi’s reign becomes increasingly unreliable.

Babylonian year names verify the Amorite Dynasty’s timeline from Hammurabi through the 27th year of Samsu-ditāna. BKL-B assigns that last king a likely correct total of 31 years, though he might have lost control of his capital in his final few years.

From 1792 through 1595 BCE, this period has almost two centuries of precisely accurate chronology. King list data becomes confused after Samsu-ditāna’s rule. Due to synchronisms between two Babylonian kings of the Amarna Period with two Egyptian pharaohs and the mistaken traditional placement of that period over a century too late, the orthodox understanding of Babylonian chronology is incorrect after 1595 BCE through the end of that millennium.

The Assyrian timeline has a slightly more extended period of correct chronology from Erišum I (Assyrian King List #33) through the first few years of Išme-Dagān I (AKL #40), the son and successor of Šamši-Adad I. An anciently recorded interval calculation (distanzangaben) gives this period two more years than the number of known limmu (eponyms), possibly representing a small error. The AKL contains no regnal period data from before Erišum I.

Only two existing copies of the standard AKL include Išme-Dagān I’s name; they grossly overstate his ruling period as 40 years. Contemporaneous data suggests that AKL compilers mistakenly combined his rule as a vassal king of Ekallatum (subject to his father) with his few years as king of Assyria. Some scholars reasonably estimated his tenure lasted 11 years. Appendix E in The Six Pillars (forthcoming) discusses the available evidence from his reign and determines the exact figure.

Consequently, the conventional understanding of the Assyrian timeline becomes erroneous for the remainder of the millennium. To make matters worse, two ruling periods of later kings (AKL #65 and 66) are missing from all copies of the AKL. As discussed in Chapter 1 of The Six Pillars, considering the generational averages in their family tree shows the sum of their reigns was only a few years. Still, conventionalists greatly expand this period, worsening the error in their chronological model.

Based on mistaken premises, the conventional understanding of Egyptian chronology is erroneous during the entire second millennium BCE! The result is that they place the New Kingdom era more than a century too late. One of their specious assumptions is that the Egyptian people used only one calendar system throughout their history without reforms or regional variations. The abundance of variant Sothic dates tells a different story. Consequently, their chronological assignment of the Middle Kingdom is too early, and they dramatically expand the Second Intermediate Period’s (SIP) length.

Since their model swings from too late in the New Kingdom to too early in the Middle Kingdom, some of their dates for a few SIP Egyptian kings are reasonably close almost by chance. For example, the Wikipedia article “Neferhotep I” lists possible coronation dates for this possibly Thirteenth Dynasty king, and the majority are sometime in the 1740s BCE. That article’s last sentence accurately states that Neferhotep I, Yantinu of Byblos, Zimri-Lim of Mari, and Hammurabi of Babylon were contemporary rulers.

Therefore, in the second millennium BCE conventional Middle Chronology model, two centuries of the Babylonian and Assyrian timelines are exactly or essentially correct. A few traditional Egyptian SIP dates are not more than a few decades in error.

One comment