Over the past 15 weeks, this website has featured 15 posts concerning “common sense” and how it leads to better solutions for chronological problems. The phrase “common sense” often implies an idea or a solution to a problem is easy and obvious. Nevertheless, common-sense solutions to ancient Middle Eastern timeline puzzles first require some degree of mastery of the material. It is usually only when we understand the related data’s length, breadth, and depth that our insights become sufficient that something previously hidden becomes obvious.

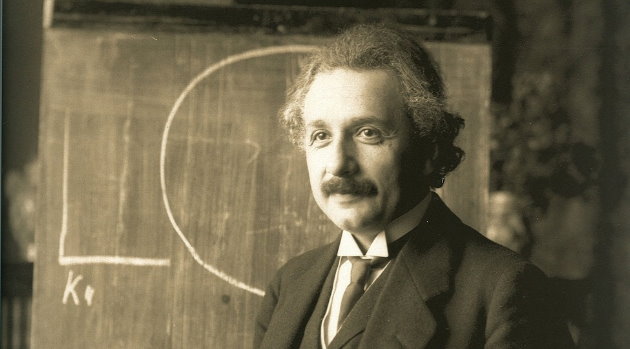

For this reason, academic Kate Sanborn (via Thomas Edison) said, ‘Genius is 2% inspiration and 98% perspiration.’ This principle applied to the work of Albert Einstein. He developed many new ideas in physics that required a genius-level IQ, but his success was primarily due to his love of the subject and a vast amount of hard work. Fortunately, ancient Middle Eastern chronology does not require such high intelligence. (If it did, I would not be qualified.) However, the 2% that Ms. Sanborn spoke about results from employing critical and lateral thinking techniques and asking questions others have not thought or dared to ask. The 98% is all the time and effort spent on research and meditation. During this in-depth investigation, common-sense solutions often emerge. When arriving at these insights, researchers frequently ask themselves, “Why did I not think of this before?”

It is much easier to deduce such solutions when topics are simple than when they are more complex. I can illustrate this idea with two personal examples:

When I considered the Mari Eponym Chronicle’s solar eclipse during the time of Šamši-Adad I, the focus of the research seemed obvious. A fragmented cuneiform tablet preserved an eponym next to the annual event “King Šamši-Adad’s birth,” and the following year’s outstanding event was a solar eclipse. Two previous eponyms were also on the tablet but without chronicle events, suggesting they might not have been original. When I compared these eponyms with the Kültepe Eponym List, only one solution seemed possible, and it was early in Šamši-Adad’s reign as king of Assyria, which led to the conclusion that his “birth” was idiomatic. Arriving at this common-sense solution took less than a day because it was not a complex problem. Nevertheless, disproving the conventional understanding and finding additional astronomical and historical data to prove this alternative model took months of research.

In contrast, I initially spent about six months studying chronological clues in the Amarna letters and determining the messages’ sequential orders. After taking a two-year break from this topic, I returned to it and spent another six months checking and revising my work. After spending almost a year studying the Amarna letter corpus, I suddenly realized what perhaps should have been obvious. Since Amenhotep IV (Akhen-Aten or Akhenaten) transported a 13-year foreign correspondence archive from Thebes to his new city, Akhet-Aten (Amarna), Tutankhamun must have done something similar when he moved his capital back to Thebes. Which year’s correspondence did he arbitrarily decide to make the cut-off date? Since no credible evidence in the Amarna letter corpus indicates Akhenaten or his successors received any of those messages later than his Year 5, that must have been Tutankhamun’s starting date for the archive he transported to Thebes. I had been so wrapped up in minor details for months that I had missed the overriding picture. Then I asked myself, “Why did I not think of that before?”

In both examples, the solution involved common sense, a questioning mind, and critical and lateral thinking. In the first instance, arriving at the initial solution was easy because it merely required looking for the correct eponym and a temporally related high-magnitude solar eclipse over Mari. In contrast, in the second instance, mastering the material took over a year of research. Using common sense (basic logic) first required deep insights into a complex dataset.

Successfully deriving common-sense solutions for ancient Middle Eastern chronological puzzles requires independence from traditions, i.e., a willingness to question everything. It also needs time to thoroughly understand the data and meditate on the material’s interconnectedness. (That corresponds to Sanborn’s 99% perspiration.) Although there are a few exceptions in which discoveries are relatively easy to derive, most require a lot of hard work.