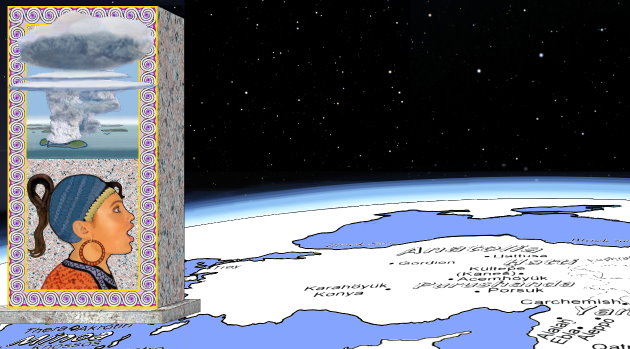

The volcanic eruption on Santorini Island (or Thera) in the Aegean Sea was probably the largest in recorded history. It had a significant and devastating impact on the Minoan civilization. But it also had widespread effects around the eastern Mediterranean. Researchers have debated when exactly it occurred. Why? They think it is a crucial date in the second millennium BCE Middle Eastern chronology that might lead to unifying the chronologies of the Egyptians, Minoans, and other Late Bronze Age cultures. Furthermore, it plunged the world into a volcanic winter lasting at least two years, and it continued to affect climate conditions for over a decade. Thus, this event had adverse effects across Asia as well.

Although the Thera eruption is not an overriding answer to mid-second millennium BCE chronology, that event and its related data constitute one of several key networks of evidence. In The Six Pillars of Second Millennium BCE Middle Eastern Chronology (to be published within the next few months), this event and the related evidence comprise the “Sixth Pillar.”

Some lines of scientific evidence point to 1650 BCE as the precise date of the eruption, and others verify that this date is approximately correct. Among them is one conclusive argument based on indirect astronomical evidence that proves the eruption occurred that year. Egyptian documents provide clues about the year’s solar eclipse and lunar cycles and how they relate to this historic event. These astronomically related conditions provide circumstantial evidence supporting 1650 BCE as the correct date. Although these two Egyptian-data-based contentions are weak, since both are true, they further verify the eruption that year was Thera, not another volcano. The homepage of this website reveals the exact month and day of this event. Chapter 8 of The Six Pillars thoroughly discusses this topic and the evidence network comprising the Sixth Pillar.

Additional historical evidence from Mesopotamia, India, and China supports this idea. A previous post discussed the Venus Tablets and the accuracy of the Middle Chronology model. Why did the Babylonians suddenly take such an intense interest in the planet Venus during the reign of Amorite King Ammi-şaduqa? He inherited the throne about three years after the Thera explosion. Furthermore, the Babylonians associated Venus with the fertility goddess Ištar (or Inanna). Through her mythological relationship with Dumuzi, the Mesopotamians also connected her with the change of seasons and farming, which the eruption disrupted. The Babylonian astronomers seemingly followed the rising and setting of Venus to derive clues about when warmer weather would return, and farming and harvests would normalize.

Archaeologists associate the Thera eruption with the early Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty, and this deduction is correct. However, most Egyptologists believe this dynasty began around a century after 1650 BCE, which is an erroneous conclusion. Radiocarbon dating from Upper and Middle Egypt seemingly contradicts dating the eruption to 1650 BCE. Nevertheless, contemporaneous Lower Egyptian radiocarbon dates are harmonious with 1650. Some of the variant radiocarbon dates from Santorini are compatible with this date, whereas others are not. (The forthcoming free e-book, Scientific Explanations for Radiocarbon Offsets at Astronomically Dated Sites, proposes theoretical reasons for these discrepancies.) An important lesson from these contradictions is that researchers should not base a chronological model on only one data type. Instead, we need multiple evidence networks comprised of intermeshed documentation to derive a convincing model. That is precisely what The Six Pillars does.

Yes, the correct understanding of when the Thera eruption occurred does provide a unifying date in ancient Middle Eastern chronology. Yet, it would not be thoroughly convincing without the additional five evidence networks (the other five Pillars) that independently or semi-independently support the same date.