(Modified 7 May 2025) The last post discussed the evidence that seemingly links the eruption of Thera with events during the transition from the Chinese Xià Dynasty (夏朝 Xiàcháo) to the Shāng (商朝 Shāngcháo).

The Bamboo Annals describe two types of events associated with this transition period that might be related to the eruption. It states that in the 29th year of the last Xià Dynasty king, Xià Jié, “three suns appeared together,” describing a sun dog. It also detailed that a drought began in the 19th year of Chéng Tāng (成湯) and lasted into his 24th year. Those years were his second through seventh years as the first emperor of the Shāng Dynasty. However, admittedly, neither sun dogs nor droughts are necessarily the consequences of volcanic eruptions. (I witnessed sun dogs twice during recent winters.)

Still, as noted in David Pankenier’s article about the effects of the Thera eruption in China (pp. 771-3), later writers such as Mozi 墨子 connected severe climate effects with the Xià-Shāng transition period. Did the sun dog, drought, and other climatic events recalled by later writers result from the Thera eruption? If that event did occur during this transition period, Shan Ling’s chronological model, discussed previously, must be correct or at least approximately so. This post presents an alternate model that is likely precisely accurate.

The Bamboo Annals briefly mention an astronomical event in the 10th year of Xià Jié: 五星錯行 wǔxīng cuò xíng, which could mean “The five [visible] planets chaotically moved.” Centuries later, some commentators incorrectly understood this was another instance of the five planets aligning as it had done in May 1059 BCE. They believed this event was another Mandate of Heaven (天命 Tiānmìng), which indicated a virtuous leader should overthrow the corrupted Xià Dynasty. Based on the 516.33-year cycle of the triple conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars, they calculated that 五星錯行 had occurred in 1576 BCE, and they incorrectly concluded that it was Xià Jié’s 10th year. This understanding led to the erroneous conclusion that the Shāng Dynasty had lasted approximately five centuries. (Cf. Pankenier, 1981, pp. 17-21.)

Author Shan Ling 凌山 noted that a source (Yù Zǐ 鬻子) contemporary with the final emperor of the Shāng Dynasty, Dì Xīn (帝辛), wrote that this monarch’s tenure began 576 years after Chéng Tāng’s. The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project assigned Dì Xīn’s first year of rule to 1075 BCE. Counting back 576 years places Chéng Tāng’s defeat of Xià Jié during his 31st and final year in 1651 BCE. With the assumption that Chéng Tāng’s first year as the new emperor (his 18th year as a regional king) was the following year (1650), four additional pieces of the puzzle fall into place with this first piece:

Second: As mentioned in the previous post, Shan Ling 凌山 cited Liú Xīn 劉歆, who stated the duration of the Shāng Dynasty was 629 years. Thus, he wrote that this dynasty lasted from 1675 to 1046 BCE. In a private communication, Shan Ling kindly provided the source of the triple combination (甲子朔旦冬至) of a winter solstice, astronomical dark moon, and first day (甲子) of the Gānzhī (干支 sexagenary) cycle, which was Volume 21 of The Book of Han. The first-century-CE author, Bān Gù 班固, commented on some chronological viewpoints of other scholars and offered a corrected understanding. He wrote that this 629-year period ended in the fifth year [1038 BCE] of Zhōugōng (周公, the “Duke of Zhou”), which was several years after the Shāng Dynasty’s end in 1046 BCE. With this premise, that dynasty began in 1667 BCE, 16 years before Chéng Tāng’s 17th year and his defeat of Xià Jié in 1651.

Third: The severe drought during Chéng Tāng’s 19th through 24th years occurred in 1649-44 BCE, immediately after the Thera eruption in 1650.

Fourth: Two out of three aspects of Shan Ling’s triple combination (甲子朔旦冬至) did occur near the end of his 12th year as emperor. In January 1638, the winter solstice was at 23:25 on 3 January, and the astronomical dark moon occurred at 03:50 on 4 January, just a few hours later. Nevertheless, neither date was the first day of the Gānzhī cycle, 甲子. Bān Gù’s sexagenary cycle dates were unreliable. A comparison of his other Shāng Dynasty Gānzhī cycle dates with dated Oracle Bone inscriptions of astronomical events proves they do not harmonize.

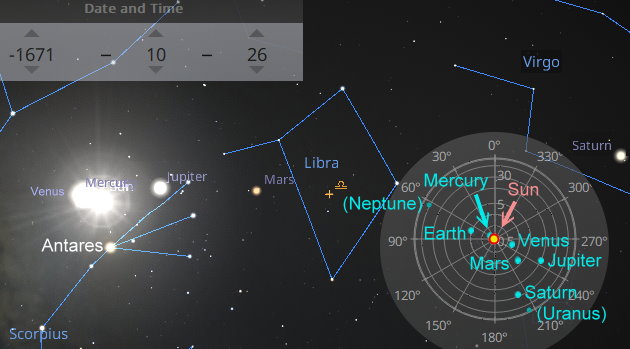

Fifth: With Xià Jié’s 31st year in 1651 BCE, his 10th year was in 1672. Professor Pankenier translated 五星錯行 as “crisscrossing planets” because “crisscross” is another meaning of 錯 cuò. In this context, cuò could connote planetary invisibility when the planets are too near the Sun to be visible and cross between their heliacal setting in the west and heliacal rising in the east. Moreover, Pankenier linked this event with “Great Fire,” the star Antares in the Scorpius constellation. (1981, pp. 18-19, 21)

The illustration above shows this occurred in 1672 BCE when the Sun’s position was next to Antares. Mercury was transiting the Sun, and Venus was crossing in the opposite direction on the far side of its orbit; thus, the two planets literally crisscrossed. Moreover, Saturn had recently crossed from evening visibility to morning, and Mars and Jupiter were in the process of doing so. Four of the five planets were invisible in the night sky.

This discussion reveals that two distanzangabens, one contemporaneous, precisely fit the premise that the Thera eruption occurred in the Xià-Shāng dynastic transition period, and two sets of astronomical details provide additional supporting evidence of this model’s accuracy. Since five puzzle pieces fit together harmoniously, we can conclude with almost 100% certainty that Chéng Tāng’s first year as a duke was 1667 BCE, and his first year as emperor was 1650 BCE.

BCE 1638.01.03/04 is JiWei/GengSheng己未/庚申。there are no other dates near jiazi 甲子 with dark moon and winter solstice triple combination in 1500-1700 BCE.

Not sure how you got Sept 10, 1650 BCE as the volcano eruption date. Is it possible to be in the 29th year of Xia Jie, i.e., 1664 BCE?

Thank you for your questions, as well as your research and articles.

The 10 September 1650 BCE date for the Thera eruption has its basis in multiple lines of scientific evidence, and they identify the specific year and the season as late summer. Babylonian evidence generally verifies the date. The chronology of The Six Pillars shows that the date was during the reign of Egyptian king Ahmose I, and two lines of internal evidence point to the same year as the date of the expulsion of the Hyksos from the Delta region. The Tempest Stela verifies that massive flooding occurred during his reign. Moreover, clues from Egyptian sources identify the exact date of the eruption. Consequently, the volcanic rain and tsunamis coincided with the peak annual flood, explaining the destruction of the Hyksos capital city, Avaris. Each of the six Pillars consists of multi-layered networks of evidence that are chronologically interlinked, culminating in the date of the Thera eruption, the sixth Pillar. You can be confident of the precise accuracy of that date.

As pointed out in this revised post, we must consider the accuracy of chronological records. Middle Eastern records have many examples of later efforts to reconstruct ancient chronology, but those centuries-later documents are often erroneous. The same is true of later Chinese efforts to rebuild their historical timelines.

As you know, the Chinese did not use the 干支 system for a 60-year cycle until several centuries after the Shāng Dynasty ended. Yet, the Bamboo Annals have 干支 year-names for the first year of each Shāng Dynasty king and even those of the earlier Xià Dynasty. Obviously, later researchers extrapolated that system back in time based on their conventional understanding of Chinese chronology.

The use of the 干支 system for a 60-day cycle had a much earlier origin. The Oracle Bones of the thirteenth century BCE have many examples of its use. I tried to find contemporary evidence of its use before 1300 BCE but could find none. Even if it did exist, the different provinces could have used it with different orientations. Thus, we would need contemporaneous evidence of its veracity to use centuries-later references to that cycle as historical evidence for establishing an absolute chronology. Otherwise, those 干支 days could be retro-calculated.

Your research identified the crucial detail that 576 years had passed from Chéng Tāng to Dì Xīn, and it came from a contemporaneous source. Therefore, this datum is far more probable to be correct, and this post provides convincing, corroborating evidence that it is accurate. These details suggest that the combination of a winter solstice and an astronomical dark moon came from a contemporaneous record. Nevertheless, the 干支 day (甲子) probably resulted from a later retro-calculation, though plausibly a contemporaneous but different 60-day cycle.

【The 10 September 1650 BCE date for the Thera eruption has its basis in multiple lines of scientific evidence, and they identify the specific year and the season as late summer.】

If this date (Sept 10, 1650) is correct, then this eruption was not correlated to the severe drought happened in Xia/Shang dynasty transition time, which was 1660-1655 BCE, determined by triple combination of 甲子朔旦冬至 Jiazi/new moon day/winter solstice 1649.01.05 BCE at the last year of Emperor ChengTang.

Hi, Shan Ling.

Thank you for your assistance in identifying the source of the record concerning 甲子朔旦冬至。 In your model, you found a way to harmonize the 629-year and 576-year interval calculations (distanzangabens) and the Gānzhī-day-one/winter-solstice/dark-moon combination. After studying Volume 21 of The Book of Han, I realized that the author, Bān Gù, understood the 629-year distanzangaben in a way that also harmonized with the 576-year interval but disagreed with your model. Moreover, his explanation perfectly harmonizes with the Thera eruption date, the six-year drought that started in Chéng Tāng’s second year (as reported in the Bamboo Annals), and the other effects of the eruption that Mozi recorded.

Since the basis for the Thera eruption’s absolute date is scientific and historical and entirely independent of Chinese data, this agreement is incredibly unlikely to be coincidental. Since Bān Gù’s Gānzhī-day dates do not harmonize with the Oracle Bone inscriptions from the late Shāng Dynasty (as interpreted by the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project), the records he consulted must have had retro-calculated Gānzhī dates. Still, the combination of an astronomical dark moon and winter solstice is relatively rare, and on 3-4 January 1638, they were only hours apart. The fact that this date also harmonizes with this model strongly suggests these two aspects of the 甲子朔旦冬至 record were historical.

Some researchers have proposed that the concept of the Mandate of Heaven 天命 was a doctrine that originated in response to the May 1059 BCE conjunction of planets and the political circumstances at the time. Later, scholars tried to retroactively apply this idea to the reigns of Xià Jié and Yǔ (the first emperor of that dynasty). This alternate hypothesis permits other possible interpretations of “five planets crisscrossed.” With this Thera-eruption-date-distanzangabens-based model, the harmony of this idea with the celestial event on 26 October 1672 BCE is also extremely unlikely to be coincidental. Consequently, the compatibility of these five data points results in a nearly 100% certainty that the dates in this post are absolute. Thus, researchers can use them as pivotal points for establishing more accurate dates for the Shāng and Xià Dynasties.

I will not remove the previous post, “The Thera Eruption as a Pivotal Point in Chinese Chronology,” which follows your model. That explanation is plausible but far less likely to be correct.